Editor: Predrag M. Maksimovich, MD, DDS, ENT.

In this Online Journal we will publish various articles, comments, letters, etc in several languages. Where possible, translation to English will be provided.

All Medical Professionals visiting these pages are urged to contribute.

Materials should be sent to our e-mail address in .htm, WP6.0 or WFW 6.0 formats while the pictures should be in .jpg and .gif.

All comments, letters, suggestions are welcome.

The floor of the mouth as a whole is bounded by the oral mucosa and tongue superiorly and medially, the mandible anteriorly and laterally, the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia with its tight attachment to the mandible and hyoid bone laterally and inferiorly, and the hyoid bone inferiorly. The submandibular space, or one of its components, is perhaps the space most commonly involved by significant primary infections of the head and neck. Infections may arise from injuries to the floor of the mouth, sublingual or submandibular gland sialoadenitis, or infections from the roots of the mandibular teeth.

Ludwig's angina is a rapidly spreading cellulitis that usually begins in the submandibular space, resulting from an infected molar, and then rapidly spreads to involve the sublingual space, usually on a bilateral basis. With the mandible and superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia presenting relatively unyielding barriers superiorly and laterally, the tongue is forced upward and posteriorly, giving rise to the severe airway obstruction associated with this condition. Submandibular space infections may also spread posteriorly to the carotid sheath or retropharyngeal space, or both, by crossing the lateral pharyngeal space.

As will be seen, the majority of cases of Ludwig's angina are of dental origin, with the development of a submandibular infection that then progresses to involve the sublingual space. Crucial to this process is the relationship of the mandibular dentition to the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle along the mylohyoid ridge. The anterior teeth and first molars regularly attach superior to the mylohyoid insertion, and infection arising from these tooth roots commonly results in a relatively limited sublingual abscess. The second and third molar roots are routinely below the mylohyoid ridge, and infection presenting on the lingual surface will enter the submandibular space. Additionally, it is important to recognize that the roots of the anterior teeth and first molar approximate the lateral mandibular surface, whereas the second and third molar roots approach the lingual surface of the mandible.

Ludwig's angina usually develops from dental or periodontal infection, especially of the 2nd and 3rd mandibular molars. It may occur in association with problems caused by poor dental hygiene (i.e. gingivitis and dental sepsis), tooth extractions, or trauma (i.e. fractures of the mandible, lacerations of the floor of the mouth, peritonsillar abscess).

Although not a true abscess, Ludwig's angina resembles one clinically and is treated similarly. Untreated, it may be fatal.

The major manifestations are pain in the area of the involved tooth; severe, tender induration of the submandibular region; trismus; dysphonia; drooling and inability to swallow; and dyspnea and stridor from laryngeal edema and tongue elevation. Fever, chills, and tachycardia are usually present. X-rays of the head and neck are useful to assess the degree of soft-tissue swelling and airway obstruction.

The infection is often caused by a hemolytic streptococcus, although the infection may be a mixture of aerobic and anaerobic organisms, which may account for the presence of gas in the tissues. Chills, fever, increased salivation, stiffness in tongue movements, and an inability to open the mouth herald the infection. Thickness is found in the floor of the mouth, and the tongue is elevated. Tissues of the neck become boardlike.

The patient develops a toxic condition, and respiration becomes difficult.

The larynx is edematous.

As the swelling progresses, there is increasing encroachment upon the airway, and the patient assumes an erect posture with tachypnoea. Dyspnea and stridor signal the imminent danger of airway obstruction. This is truly a desperate situation because visualization of the larynx by conventional techniques is impossible, and attempts at intubation may actually precipitate airway obstruction. Similarly, a tracheostomy is extremely difficult because of the inability of the patient to lie supine and the presence of significant neck edema. The point to stress is the rapidity with which this process may occur; many case reports detail a progression from onset of symptoms to respiratory obstruction within the space of 12 to 24 hours.

The submandibular and submental regions are tense, swollen, and tender. The floor of the mouth is tense and indurated, with massive mucosal swelling and pouting of soft tissue over the edges of the lower teeth. Fluctuance is unusual. The tongue is pushed superiorly, and there is marked trismus.

Indirect examination of the larynx is, at best, difficult and usually impossible. Nasopharyngeal fiberoptic examination will reveal the presence of a greatly enlarged base of the tongue pushing the epiglottis posteriorly; the supraglottis and endolarynx are normal in appearance.

Develops along fascial planes with direct extension; does not involve lymphatic spread

Does not involve submandibular gland or lymph nodes

Involves both sublingual and submaxillary spaces and is usually bilateral

Ludwig's angina may be described as an overwhelming, generalized septic cellulitis of the submandibular region. Although not seen often, Ludwig's angina, when it does occur, usually is an extension of infection from the mandibular molar teeth into the floor of the mouth, since their roots lie below the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle. It is usually observed after extraction.

This infection differs from other types of postextraction cellulitis in several ways. First, it is characterized by a brawny induration. The tissues are boardlike and do not pit on pressure. No fluctuance is present. The tissues may become gangrenous, and when cut, they have a peculiar lifeless appearance. A sharp limitation is apparent between the involved tissues and the surrounding normal tissues.

Second, three fascial spaces are involved bilaterally: submandibular, submental, and sublingual spaces. If the involvement is not bilateral, the infection is not considered a Ludwig's angina.

Third, the patient has a typical open-mouth appearance. The floor of the mouth is elevated, and the tongue is protruded, making respiration difficult. Two large potential fascial spaces are at the base of the tongue, and either or both are involved. The deep space is located between the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles; the superficial space is located between the geniohyoid and mylohyoid muscles. Each space is divided by a median septum. If the tongue is not elevated, the infection is not >considered a true Ludwig's angina.

Pathognomonic for Ludwig's angina is the sign of cock's crest. Sometimes unilaterally but usually bilaterally the floor of the mouth is red and swollen and a streak of yellow fibrin covers sublingual carunculae so that it looks as if a cock is protruding his red head with a yellow crest from below the tongue. It can be stated safely that if the mucosa of the floor of the mouth is normal there is no Ludwig's angina.

Surgical treatment is directed at securing an airway and providing surgical drainage. The choice of airway management rests on the experience and availability of the treating personnel. Although airway management by nasotracheal intubation, with or without fiberoptic assistance, is well described in the literature, it should be borne in mind that airway manipulation may precipitate acute obstruction and, thus, a tracheostomy set should always be available. Because of the possibility of postoperative extubation, and the difficulty of reintubation, conversion to a tracheostomy is generally advocated for postoperative airway management. If intubation is not possible, a tracheostomy under local anaesthesia, often with the patient sitting upright, is required. This may be complicated by the presence of significant edema in the neck. Those patients with a rapidly deteriorating airway may require a cricothyroidotomy.

Once the airway is established, surgical drainage is performed.

Drainage consists of a wide surgical decompression of the suprahyoid region. Generally, the infectious process is bilateral, and the approach is through a median, horizontal incision three to four fingerbreadths below the mandibular margin. The length of the incision may be variable, but generally it crosses to the submandibular region bilaterally. The mylohyoid muscle is split in the midline, and drainage is established both medially and laterally. Often, the side on which the infection started needs to be explored with decompression of the submandibular capsule and blunt dissection to the mandibular margin. The tissues have been described as having a peculiar "salt pork" appearance, with woody induration, watery edema, and little bleeding. Gross purulence is rarely encountered at the time of exploration but will often drain from the wound several days after decompression. Multiple drains are placed, and the wounds are left open.

The choice of antibiotics must be tailored to the individual patient, but high-dose penicillin (12 to 16 million units/day) is considered the drug of choice. Chloramphenicol and clindamycin are alternate possibilities, especially in penicillin-allergic patients. In immunocompromised patients, consideration should be given to providing broader coverage for the possibility of gram-negative anaerobic organisms and penicillin-resistant staphylococci.

Tracheostomy (either initially or after intubation) is generally considered the safest means of maintaining an airway. Following acute airway obstruction, the next major potential complication of Ludwig's angina is extension of the infection to the carotid sheath or retropharyngeal space with inferior extension into the mediastinum. Although extension to the mediastinum was formerly common, it is somewhat unusual with present-day surgical drainage and antibiotics. Extension of Ludwig's angina should be suspected if there is persistent or increasing neck edema, spiking temperatures, or persistent leukocytosis. Later findings of mediastinal extension include increasing signs of septic shock with tachycardia and decreasing blood pressure, crepitation of the lower neck, or development of mediastinal crepitation or a mediastinal crunch. The patient with mediastinitis will often report increasing neck pain, chest tightness, and increasing dyspnea. The chest x-ray film may show a widened mediastinum, pericardial air, pulmonary infiltrates, and extrapleural fluid. As mentioned, in the acute phase of Ludwig's angina, there is little or no purulence because of the fact that the infection is developing so rapidly that there is no time for pus to develop; later it is common for purulence to drain from the wounds. It is also possible that isolated, undrained pockets of pus may develop, which may give rise to continuing signs of sepsis. A CT scan of the neck with contrast medium may be most helpful in detecting these residual pockets and directing surgical drainage.

Other complications can include asphyxiation, aspiration pneumonia, lung abscesses, and metastatic sepsis.

![]()

Case Reports

Several other patients.

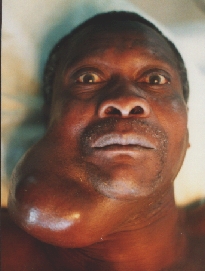

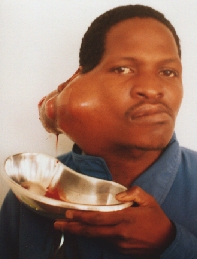

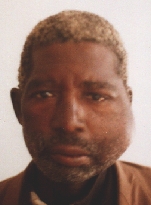

Cystadenocarcinoma of the RT submandibular gland.

Recurrence one year after the first operation.

![]()

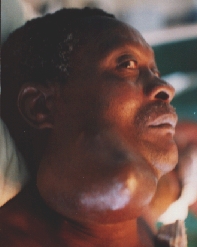

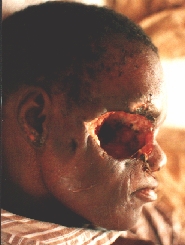

Cystadenocarcinoma growing for about four years. Notice the ophthalmoplegia.

![]()

![]()

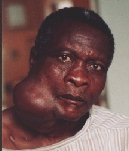

The patient immediately after LT hemimandibulectomy with exarticulation from the second LT premolar tooth for carcinoma involving LT trigonum retromolare, anterior LT tonsil and LT angle of the mandible. Notice the deviation of the mandible to the left.

Intraoral wound healing mainly per secundam. One vicryl sutur is still visible.

Recurrence in the LT cheek one year after the first operation. Removed with radical parotidectomy.

![]()

State after removal of the tumor of the LT lower eyelid and zygomatic area with reconstruction with local rotational flap. Notice the defect of the eyelid, ektropion and scar.

![]()

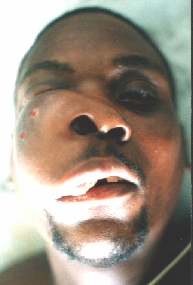

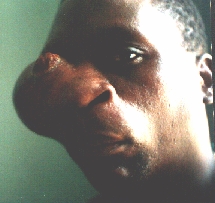

Squamocellular carcinoma destructing the nos and extending per continuitatem to the upper lip, both cheeks and both peri- and submandibular regions.

After partial amputation of the nose and upper lip.

![]()

Squamocellular carcinoma destructing almost whole of the body of the mandible.

Primary reconstruction achieved with transpositional regional flap from the neck. Lower cortex of the mandible was retained to keep the space.

![]()

Epulis.

![]()

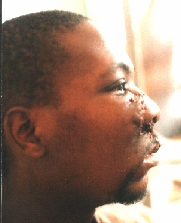

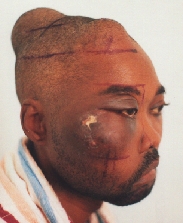

A patient from the rural areas treated for a long time for an "eye infection". Alleggedly, eye globe was removed.

An orbital exenteration was performed. A structure similar to a shrunken eye globe was also removed. Histology: carcinoma.

Some six months after the first operation a local recurrence in the temporal region is evident.

![]()

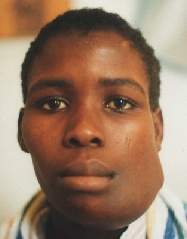

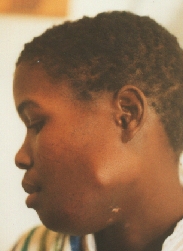

LT parotid cystadenocarcinoma.

Scar is visible after a biopsy (sic!!!) performed in other hospital. Superficial parotidectomy was done with preservation of the facial nerve and the scar with the surrounding skin was included with the specimen.

![]()

CT scan showed a lesion the size of a fist in the anterior RT frontal lobe.

During the first operation,

black masses were removed.

Histology: blastomycosis.

During the second operation the neurosurgeon removed the tumefaction

from the anterior lobe.

![]()

Sarcoma maxillae.

After the first operation.

Six months later the patient appeared with even greater tumour.

After the second operation.

![]()

Pharyngeal fistula after irradiation and total laryngectomy for laryngeal carcinoma.

Reconstruction with Ariyan's pectoralis major musculo-cutaneous flap. Notice the elevation of the Bakamjian's delto-pectoral flap for possible future use.

Incipient necrosis of the flap above the tracheostomy.

![]()

Terminal stage of the laryngeal carcinoma with fungiform recurrences.

![]()

Plasmacytoma undergoing (unsuccessful) radiotherapy.

![]()

![]()

Ameloblastoma.

![]()

![]()

® Copyright, 1998.

All Rights Reserved.

SigmaMax Publishing.